Leaving Lummus

Lummus was a great place to start a career and learn as much as possible as quickly as possible. It was a good time to be working in the oil and gas industry since the previous downturn was just ending and the inevitable upturn was well underway. I had the opportunity to work for and alongside some great engineers and innovators and really hone my engineering skills. After nearly ten years, however, I started to become somewhat disenchanted with both the company and the corporate environment in general.

Let’s put it this way. When I joined Lummus as a junior engineer there were three slots between myself and Vice President. Nine years later I had been promoted several times but there were now ten slots between myself and the Vice Presidents. The company had four Vice Presidents when I joined. Now there were, unbelievably, fifty-seven Vice Presidents. The main activity was no longer carrying out engineering but rather sitting around in conference rooms telling each other we’re here to make sure “we do this right” whatever that was supposed to mean. You couldn’t even book a conference room. They were all occupied with Lummus guys posturing and bullshitting all day long.

For my first few years at Lummus, I was involved in the engineering and design of lube oil plants. It was a good experience and I learned a lot but it was not an upward career path in Lummus. Lummus prided itself on being a premier technology company. A company with a broad portfolio of proprietary and patented technologies that provided a distinct advantage over its competitors. Lube oil technology was not one of those technologies. The basic technology and know-how were actually owned and licensed by Texaco, not Lummus. We merely executed the process and mechanical designs based on Texaco’s guidelines. My other projects besides lube oils were oil refinery design and engineering assignments. Again, great experience but as with lube oils, these were mainly proprietary processes, usually licensed from UOP.

The principal business of Lummus, the cornerstone technology as it were, was ethylene technology. These were large, expensive facilities that at that time were entering an early stage of massive market growth where Lummus had a distinct proprietary advantage. In the Lummus Company, ethylene was king. In my last couple of years with the company, I had the opportunity to work on a few ethylene projects but these were sporadic catch as catch can situations. By this stage in my career, I was essentially a petroleum refinery expert.

The Lummus ethylene group was large and well-staffed and for me becoming a full-fledged member of that exclusive club would be a long, arduous, and uncertain process. Instead of trying to make the transition, I opted out. I left Lummus without another full-time job. My plan was to set up a small independent consulting company and peddle my skills as a knowledgeable process engineer with experience in process design, start-up, and troubleshooting. I called my one-man company Process Systems International (PSI).

My first contract as an independent agent was with a company located in Philadelphia, Catalytic Construction. It was actually a subsidiary of Air Products and Chemicals in Allentown, Pennsylvania. I had a one-year contract with Catalytic providing process design expertise on a coal liquefaction project for Southern Company Services, a large power generation company in Birmingham, Alabama. Catalytic had a contract to design and build a power plant in Birmingham based on coal liquefaction technology. The incentive for this project was to reduce US dependence on foreign oil which had taken a drastic price escalation in the late 70’s. I was informed of the opportunity and was recommended to the Catalytic engineering team by a headhunter I had known at Lummus. his contract paid quite well and was a substantial premium over my previous salary at Lummus. It was an auspicious beginning for my newly formed enterprise, PSI.

With Jill and Jimmy getting older, the living quarters in Colonia, New Jersey with Joann’s Mom and Dad were getting quite cramped. And since my father-in-law, Herman, had recently retired there was a general consensus among the extended family that a move for all of us was in our best interests. I was strapped for disposable cash but had a large increase in monthly income from my consulting contract with Catalytic Construction so we collectively decided to move to a larger home. After some deliberation, we came up with the idea of buying a larger home in Southern New Jersey within reasonable commuting distance to Philadelphia. Home prices were more reasonable in southern New Jersey and after a bit of shopping around, we found a beautiful property in a small town within proximity to Philadelphia called Tabernacle, New Jersey.

It was a large three-bedroom house with an attached two-and-a-half car garage on several acres adjacent to the New Jersey Pine Barrens. And it featured an in-law apartment on the second floor with its own separate entrance ideal for Herman and Helen. Our plan was Herman and Helen would sell their house in Colonia providing a substantial down payment for the new house and I would carry the mortgage which I could well afford with my new project underway in Philadelphia. We did the deal and moved into our new home on Foxchase-Friendship road in Tabernacle; Joann, the kids, and I on the first floor and Herman and Helen on the second floor in their own in-law apartment.

The house was located on an unpaved road across from a Girl Scout camp, Camp Inawendiwin, and adjacent to a quarter million acres of undeveloped pine forest, the so-called Jersey Pine Barrens. It was an ideal place to raise a young family offering unlimited recreational activities at our doorstep. We could hike, fish, canoe, and let our dogs could run free in the immediate surroundings and we would still be within one hour drive to downtown Philadelphia to the west and the Jersey Shore to the south.

My folks thought I was an idiot. My Dad complained about the unpaved road and mocked the name of the town, thought it sounded like some kind of religious cult – Tabernacle. He was wrong, it was a great place, and moving there was one of the best decisions I made and in many ways one of the happiest and most contented times in my life.

There was a very large partially finished and fully carpeted basement in the house where the kids could play to their hearts’ content. It was an “L” shaped basement, walled off where the utilities including the furnace and well water pump were located. This utility area had a separate entrance from the backyard and I built a sturdy bench and located my workshop there. Eventually, I built another wall which created a sizable room adjacent to the kids’ play area where I located my office. It included a large desk, computer table, file cabinets, and a complete wall of bookcases. It was ideal. Upstairs the house had a sunken living room with a brick fireplace at one end, a small elevated area where we located a piano, and sliding glass doors to a covered porch. There was a large kitchen and adjacent dining area with a floor-to-ceiling “walk-in” fireplace. I installed a cast iron wood stove in the fireplace to warm the dining area without compromising energy efficiency. Overall, it was our “dream house”.

I commuted daily from Tabernacle to downtown Philadelphia working for Catalytic in Center City in a high-rise office building then known as the ARCO Towers in Centre City square. I drove every day from Tabernacle to a small town called Lindenwold, where I would leave the car and take the commuter train into Center City Philadelphia. When the project at Catalytic was concluded I was able to secure contracts with several small firms in the greater Philadelphia and New Jersey area. In fact, my previous employer Lummus also hired me for several small consulting assignments.

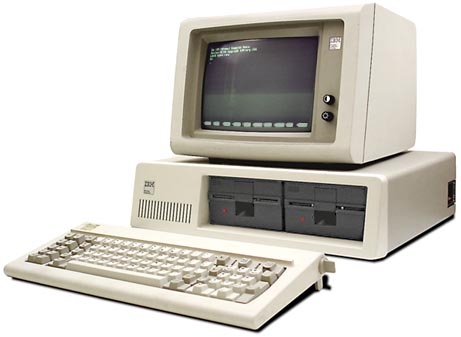

One major disadvantage of working independently was that I no longer had access to a mainframe computer to carry out detailed engineering calculations. However, there was a service available at that time called ChemShare. For a subscription fee and a very reasonable online charge, one could use a personal computer and phone modem to run chemical engineering calculations on a remote mainframe computer. So, I purchased my first personal computer, an IBM PC with 64K of memory, a single-sided floppy disk drive, a monitor the size of a small TV, and a telephone modem. The cost for the whole package was about five thousand dollars. I signed up with ChemShare and I was able to do all of my engineering calculations over the landline and effectively compete with the big engineering companies that had huge mainframe computers, the venerable IBM 360’s.

There were some problems however. Cost of the service was one. It could get expensive, especially for multiple runs or especially for mistakes that would not converge quickly. Reliability of the phone modem was another problem. The phone line might drop the connection in the middle of a run and this could run up CPU time for a solution. As a result, after a few months of struggling with ChemShare, I decided to write my own software for basic engineering calculations. I had learned FORTRAN while in Newark College of Engineering and so I started to write a FORTRAN program to carry out a basic chemical engineering calculation known as equilibrium flash calculations.

Eventually, I got a functional program working which I used to rough out calculations that I would later use ChemShare for to make a final confirmation run. This saved considerable CPU time on ChemShare. My home-grown program worked and was accurate but not very user-friendly.

I was having lunch one afternoon in a local restaurant, the Medford Diner, and I overheard a couple of guys in the next booth talking about computers and computer programming. I knew enough about computers to understand that they were accomplished programmers and understood from their conversation they had their own business. I struck up a conversation and eventually mentioned my engineering software. The two fellows were partners in a small software company in Medford Lakes, New Jersey, called Microtek Computer Consultants. Dave Soll was the president and Marc Leslie was the VP. These two guys with a couple other part-time programmers set up computer systems and wrote software for local small businesses in the southern New Jersey area.

[Note: After Hal passed away, Marc Leslie reach out to me about the creation of the software he had Microtech help him build. Marc provided this additional glimpse into my dad’s work with them at the time. David Soll passed away in November 2021 after a courageous 2-year battle with cancer.]

Engineering Software – Creating FLASHCALC

From Marc Leslie – The original project was FlashCalc, which calculated the flash point of petrochemical liquids, and Hal had taught himself to program in BASIC, the result was both funny and amazing. You could see when he learned a certain statement, like a For…. Next loop as the next ten pages of code would all be For… Next loops! But the amazing thing and this is a testament to your Dad’s intellect, is that this incredibly complex bit of programming worked! Now, he understood that the code *really* needed to be cleaned up to be commercial, which is where he contacted us, but I was always impressed with just about everything your Dad did.

Although he didn’t have a lot to do with this humorous story, he once called my wife at her office in Toledo, OH when he was with Air Products. Jeanne wasn’t available and when she returned (and this was a while ago) there was one of those pink “you need to return a call” slips with the name of the caller “Helga Nardson”. Jeanne didn’t know who this was and was very surprised when she called and your Dad and his deep voice answered and it took a while for each of them to figure out who was calling and who the other person was.