In 1986, I received a lead on a project from my associates at Lummus. A refinery in Pakistan, Attock Oil Refinery, had a problem with the composition of its feedstock. The crude oil they processed from a local oil field was changing over time; getting heavier and more difficult to process. They needed someone with experience with this problem to help develop a solution. Lummus recommended me since I previously completed a similar assignment for the Lummus-designed Concepcion refinery in Chile.

I looked into flights from the US to Pakistan and there weren’t many good options. This was an era when there had been quite a few airline hijackings around the world and I was especially cautious. I finally decided to fly on a Pakistani airliner because I reasoned it was unlikely that they would hijack or blow up their own airliner. The lesser of evils, if you will. So, I booked a flight from New York to Rawalpindi Pakistan on PIA, Pakistan International Airways. I contacted the client before I left the US and informed them of my flight and arrival time so they could arrange transportation from the airport to my hotel in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, just 30 minutes south of Islamabad, Pakistan.

The flight left LaGuardia in New York, then onto Istanbul, Turkey, and finally to Islamabad, Pakistan, just north of Rawalpindi. When I finally landed, I was a little apprehensive, to say the least. This trip took place about two weeks after President Regan had US Forces bomb Muammar Gaddafi’s Tripoli residence and one of Gaddafi’s young children was killed. I didn’t think Americans were going to be welcomed with open arms in the Middle East. Nevertheless, the deal with Attock was already signed and I felt obliged to honor my commitment.

I arrived at the airport on schedule, disembarked, and entered the queue to get through customs and immigration. As I was standing in line, I was approached by a military official in uniform and he didn’t speak to me, but took a piece of chalk and put a large X on my luggage, and moved on. Oh, oh, bad start. After he walked away, I turned the suitcase around so no one could see the X. I didn’t know what the X meant but I was the only one that had one and I was also the only westerner on the flight. I was just hoping I didn’t somehow inadvertently insult Mohammed.

Eventually, I got through customs & immigration and proceeded to the street side outside of the airport. Hot, humid, and rife with the odor that’s unique in all tropical third-world countries. There were at least a thousand people crowded outside the airport waiting to meet disembarking passengers. All were dressed in the local garb, including the rags wrapped around their head. None looked very sociable. I stood just outside the exit door for a long time waiting for someone to show up with a sign with my name, or Attock Oil, or something that identified them as my ride. No one showed up.

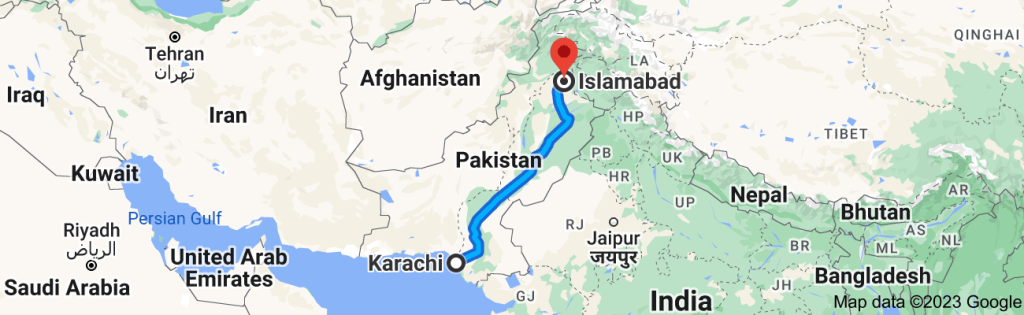

Eventually, the crowd dispersed and I was alone, on the street corner, and no ride from Attock had arrived. I found the room in the airport where the phones were located and called my contact at Attock. He said he was in Karachi waiting for me at the Airport. Karachi is almost a thousand miles south of Rawalpindi! WTF?

He said he would contact someone in Rawalpindi to pick me up and take me to the hotel where they had booked a hotel room. In due time, someone did show up, however, I was then within an “inch” of turning around and getting on the next flight the Hell out of there. Not a very auspicious start for this assignment.

The following day, I arrived at the refinery, met the top management, the engineers, the plant operators, and started solving the problem. An older gentleman who worked his entire career at the refinery but was now semi-retired was assigned to be my guide & mentor. His name was Mohammed Hanif Khan. He was about seventy years old, a PhD Chemical Engineer who worked his entire career at the Attock refinery and was very knowledgeable about the current refinery, as well as its history.

I was in Rawalpindi for nine weeks working on the solution to their crude oil problem and Mohammed was my constant companion and source of information. We worked well together and over the nine weeks that I was there we developed a close friendship. In fact, he invited me to his home after work on several occasions to meet his wife and his oldest daughter, a medical doctor in Karachi. After dinner, he and I would relax in his den/library often discussing the project, as well as other common engineering and technical interests. I wondered how we became so close in such a short time and one night he told me a story that explained it.

He said he “took his Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in 1949”. He further told me that “He was very apprehensive about attending graduate school in the US as he didn’t speak English very well, he was a brown guy and didn’t know whether he would fit in”. He took a rented room in a small rooming house near the campus and the house was owned by a family named Larson. Despite his reservations, he told me that the Larsons’ took him in like a son and helped him immensely in every way. He opined that “he thought the Scandinavian people were the best example of mankind.” I then realized that Mohammed, by helping me as he did, was paying back a fifty-year-old debt. Since I have a Scandinavian surname (Gunardson), he immediately imagined, in his mind, that I was sent there for a reason. I understood that at the time but now at the age of seventy-two, I can fully appreciate it.

Trip to the Northern Frontier – The Khyber Pass

On the weekends, which are Friday and Saturday in the Middle East, the company would provide a car and driver to take me to a hill station, as they called it, to relax and recharge. The Hill Station was an impressive old stone building at about 3,500 feet elevation, part way up the Spin Ghar Mountains that separate Pakistan from Afghanistan. The range connects directly with the Shandūr offshoot of the Hindu Kush mountain range. It’s located about three miles from the Afghan border near Landi Kotal.

The Khyber Pass, one of the oldest passes in the world, is part of the Silk Road which throughout history has been an important trade route between Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent. It has also been and still is a strategic military location.

The accommodations were in an impressive old stone building at the summit of the pass built by the British in the late 1800’s. The Pakistanis aren’t too fastidious about maintenance so the place was a bit worn down, but comfortable enough. My client, Attock Oil, owned the place so it didn’t cost me anything to stay there. As an added bonus, for my amusement, I was able to watch the Russians bomb the Khyber Pass to deter the Afghans from coming through to obtain weapons in Pakistan from the CIA. The Russians were at war with Afghanistan at that time and the US was supporting the Afghan rebels.

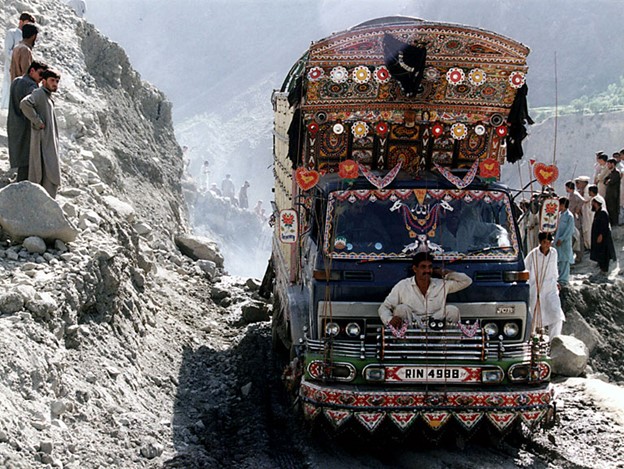

The car trip up over the pass and back again was quite an adventure. It was an unpaved road cut into the side of the mountain with a fair amount of traffic in both directions, including trucks of various kinds and buses packed with passengers both inside, atop, and hanging on the outside, as well. The backdrop for this, as I said, was the Russian bombs going off on the Afghan side of the border. This trip through the pass was definitely a unique “white knuckle” experience.

On one incident in particular, the return trip to Rawalpindi became extremely tense. We were already through the pass and somewhere in the city of Islamabad mired in heavy traffic, when we had an automobile accident. The traffic ahead stopped abruptly and my driver ran into the guy in front of him. It was one of those buses full of passengers hanging all over the outside of the bus. The collision was at slow speed, so not much actual damage was done but all traffic stopped in the middle of the road. The drivers each got out in the street and started to argue over who was at fault. In the meanwhile, the bus emptied out and a large mob of passengers and onlookers congregated around the car. And finally, they spotted me, the ‘white guy’ in the back. A large crowd were staring and pointing at me at me and a few started pulling at the door handle. None were smiling and they didn’t look all that that friendly. If ever there was a time that I wished I was invisible, this was it.

Finally, after ten minutes, which seemed like a couple of hours, my driver returned and started to drive away. He and the bus driver apparently reached an agreement about whose fault it was and who was going to pay whom and we proceeded back to Rawalpindi, and my hotel. What an incredible relief. I really thought I was finally screwed! If that crowd yanked me out of the car, not only was there nothing I could do about it, but I was entirely on my own in Pakistan and no one would even come looking for my remains.

When I got back to my hotel and had a bit of time to reflect on the situation, I decided that when this assignment was over I was going to get out of the consulting business and take a job with a company that wasn’t situated in this part of the world. Several previous job offers with Air Products were starting to look pretty attractive.

This occurred in 1986. Years later in 2002, there was an incident in that same part of the world that attracted much media attention. It was the beheading of Daniel Pearl, a journalist with the Wall Street Journal on assignment in Karachi.

“Pearl was kidnapped while working as the South Asia Bureau Chief of The Wall Street Journal, based in Mumbai, India. He had gone to Pakistan as part of an investigation into the alleged links between American Richard Reid (known as the “shoe bomber”) and Al-Qaeda. Pearl was killed by his captors.

In July 2002, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, a British national of Pakistani origin, was sentenced to death by hanging for Pearl’s abduction and murder. In March 2007, at a closed military hearing in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, a member of Al-Qaeda, claimed that he had personally beheaded Pearl. Researchers have also connected Al-Qaeda member Saif al-Adel with the kidnapping.”

A few years after this tragedy Daniel Pearl’s wife wrote a book about the murder entitled “A Mighty Heart: The Brave Life and Death of My Husband Danny Pearl”. I bought it and read it. It gave me the chills. Daniel Pearl, accompanied by his wife Marianne, spent their days before he was kidnapped traveling and living in Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Lahore, and Karachi Pakistan and she gives detailed descriptions of the streets, neighborhoods and tea houses they frequented. I frequented the same venues in 1986 and remembered them well. My experience was almost two decades earlier, but reading her account,I couldn’t help thinking, “There but for the grace of God go I”. The wrong place at the wrong time and “Boom”, that’s it. Game over.

Nuclear disaster at Chernobyl – Apr 26, 1986

I didn’t realize it at the time, but when I flew from London to Istanbul to Islamabad on Pakistan International Airways, the route took us directly over Chernobyl at the exact time the nuclear reactor was in full meltdown. I’m sure we flew right through the nuclear cloud. This consulting assignment was bad news in every way shape and form. It was definitely time to start looking for a better way to make a living.

Good luck, so long, and have a nice day!